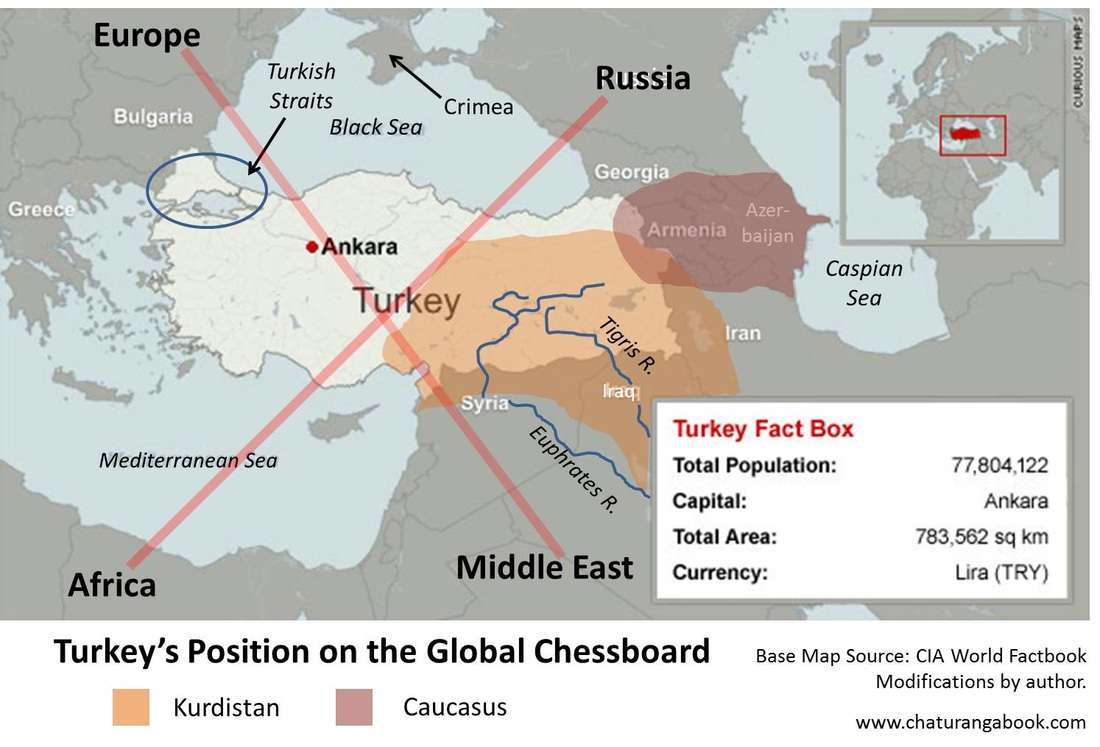

Geography and History Point to a Turbulent Future By Andrew C. Katen  Last week’s failed coup in Turkey has led to diverse speculation about which direction the country will now take, and how this course will affect the region and world. The reality is that nobody seems to know exactly what happened or why, or what will come next. In fact, forecasting near-term political events is challenging because it involves predicting the thoughts and actions of individuals – human beings that are fickle, frequently unreasonable or irrational, and often influenced by the collective mentality of their tribe. Added to this difficulty is the level of secrecy that cloaks every elite body’s decision-making and which makes interpretation of their intentions all the more difficult. Simply put, nobody today knows for sure what will happen in Turkey over the coming days, weeks, or months. Nevertheless, we can make some reasonable guesses about the long-term future of Turkey by understanding its geopolitical situation – that is, viewing the country in the context of its long history and enduring geography. We can identify deep-rooted forces that have shaped the country’s behavior and fate up until now, and whose influence will likely continue into the foreseeable future. While we do not have the benefit of a crystal ball, we can make sound assumptions based upon historical patterns and trends. There may be deviations along the way, but in the long run geopolitics usually wins out because of its defining trait: momentum. Momentum is an essential concept to remember when differentiating short-term political circumstances from longer-term geopolitical trends. A useful analogy involves a jet-ski and a cruise ship. A jet-ski is small, fast, and can change direction “on a dime.” When the rider lets off the gas, it basically “dies” in the water. On the other hand, a cruise ship is large, slow, and comparatively unwieldy. Even if its engines are cut, it will maintain its course for a considerable distance. The reason, of course, is the cruise ship’s gargantuan mass, which gives it much more momentum than a jet ski. Larger momentum means that a cruise ship will require much more force, distance, and time to stop (or change direction) than a jet-ski. With this analogy in mind, let’s take a look at Turkey’s geopolitical situation. What happens in Ankara or Istanbul over the next couple weeks or months is akin to the maneuvers of a jet-ski. The situation may change quickly and drastically; after all, the country’s immediate course will be set by the decisions of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his ruling party, and possibly by external actors, as well. While these decisions will have consequences, they will not likely alter Turkey’s larger geopolitical impetus. In combination, Turkey’s geography and history are like a cruise ship whose momentum cannot be quickly or easily altered, and whose course over the past millennia suggests that more geopolitical turbulence is on the way. Turkey is located in Anatolia, a landmass that has been repeatedly conquered by major powers since ancient times. Long before Alexander the Great, this region served as a strategic square on the world’s chessboard. It has continued to be an important land bridge between Europe and Asia, and its position astride the Turkish Straits affords whoever occupies Istanbul control over a critical maritime trade route and strategic bottleneck. In fact, many historians have speculated that the Trojan War was not really fought over a woman, but rather over this key geopolitical chokepoint. Nearly three thousand years after the Greeks fought for the Turkish Straits, Russia’s Catherine the Great recognized them as a critical gateway for Russia’s navy to access the warm waters of the Mediterranean – a reality which prompted her to seize the Crimea and establish a naval base there in the late-1700s. In actuality, her policy for the Black Sea region represented only a snapshot in a long history of geopolitical friction between Turkey and Russia. The Russo-Turkish Wars (aka, the Ottoman-Russian Wars) are one of the longest series of wars in European history, involving at least 12 conflicts waged from the 16th to the 20th centuries. Although they began as a confrontation over Ukraine, these wars soon grew to encompass wider struggles for influence over places such as the Caucasus, northern Persia (Iran), and the Balkans. Russia’s invasion of eastern Ukraine in 2014, followed by the 2015 shoot-down of a Russian warplane by Turkey, simply reaffirm that this centuries-old geopolitical rivalry is far from finished. Turkey’s ethnic history is another important geopolitical theme to keep in mind when assessing current events and future policies. Not surprisingly, the majority of the country’s inhabitants are Turkic. But they represent only one segment of a geographically diverse collection of Turkic ethnic groups that are located throughout Eurasia. Believed to have originated over 2000 years ago in what is now Mongolia, the Turkic peoples eventually migrated across Central Asia and into Eastern Europe and Anatolia. In some cases, they have mixed with existing local populations; in other instances they have coalesced into great powers that dominate the landscape; examples include the Seljuks, Golden Horde, Timerids, Mughals, and Ottomans. Today, Turkey is the world’s largest Turkic nation-state, but it is certainly not the only one. In fact, the majority of the world’s Turkic peoples are still located throughout the Caucasus and Central Asia. Most reside in the independent states of Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan; however, Turkic peoples also constitute sizeable populations of Xinjiang (aka “Chinese Turkestan”) and eastern Moldova (bordering northern Ukraine), as well Russia, Georgia, Iran, Iraq, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan. Regardless of where they live, however, the Turkic peoples are linked by strong cultural, historical, and linguistic bonds. Furthermore, most of them are Sunni Muslims. While ethnicity and Islam link Turkic peoples across Eurasia, Turkey maintains a singularly unique importance: it is also the geographic and cultural heart of the Ottoman Empire. For nearly 700 years – from roughly 1300 A.D. until the end of World War I – the Ottomans controlled much of the Middle East, as well as the Caucasus, southeastern Europe, and northern Africa. During most of this time, the Ottoman Empire also held the title of Islamic caliphate – a designation that was kept until the empire was abolished in 1924 and replaced with the Republic of Turkey. In the years that followed, founder and first president Mustafa Kemal Attatürk instituted a program of modernization and secularization, thereby supplanting Islamic decree with constitutional rule of law. Although Attatürk's guiding principles were generally upheld throughout the remainder of the 20th century, they contradict Turkey’s much longer history as a regional hegemon and center of Islamic power. Indeed, current trends are revealing Turkey’s inherent vulnerability to the ancient and powerful forces of geography, history, and culture. At the start of the 21st century, Turkey still possessed many of the criteria established by Attatürk: it was a constitutional democracy, modern and relatively secular, characterized by a strong legal framework, and guided by his noninterventionist policy of “peace at home, peace in the world.” Yet, last week’s coup highlighted the return to Ottoman-like authoritarianism that has been advancing steadily over the past decade.

Even if Attatürk’s vision for a modernist, secular Turkey survives the current instability, it does not alter the realities of the country’s deep-rooted geopolitical challenges (risks which I point out above, as well as in a 2013 article and here). The recent diplomatic disputes with Russia expose a centuries-old conflict that will not soon be resolved. As Russia and China expand into Central Asia, the Middle East’s borders unravel, militant Islam continues to spread, and Iran reemerges to pursue its own hegemonic goals, Turkey’s inherent geopolitical situation will only become more apparent. In conclusion, recent events in Turkey appear to validate the enduring significance – indeed, the enormous momentum – of geopolitics. What these events mean for the country’s future cannot be stated with certainty. That said, a return to a constitutional, secular republic – one that pursues peace and liberty in Turkey over authoritarianism and intervention in the wider Turkic region – does not fit the trend established over the past millennium. This reality does not make it impossible for Turkey to halt, or even reverse, course – but the likelihood of doing so is analagous to stopping a cruise ship “on a dime.” Geography and history are weighty forces, and Turkey’s long-term momentum will be very difficult to overcome. ©2016 Andrew C. Katen. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to share this article with others, as well as to print or post it on other websites, so long as credit is given to the author.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorAndrew C. Katen Archives

November 2016

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed